Olga Grotova

Our Grandmother’s Gardens

The Rencontres d’Arles, 2022

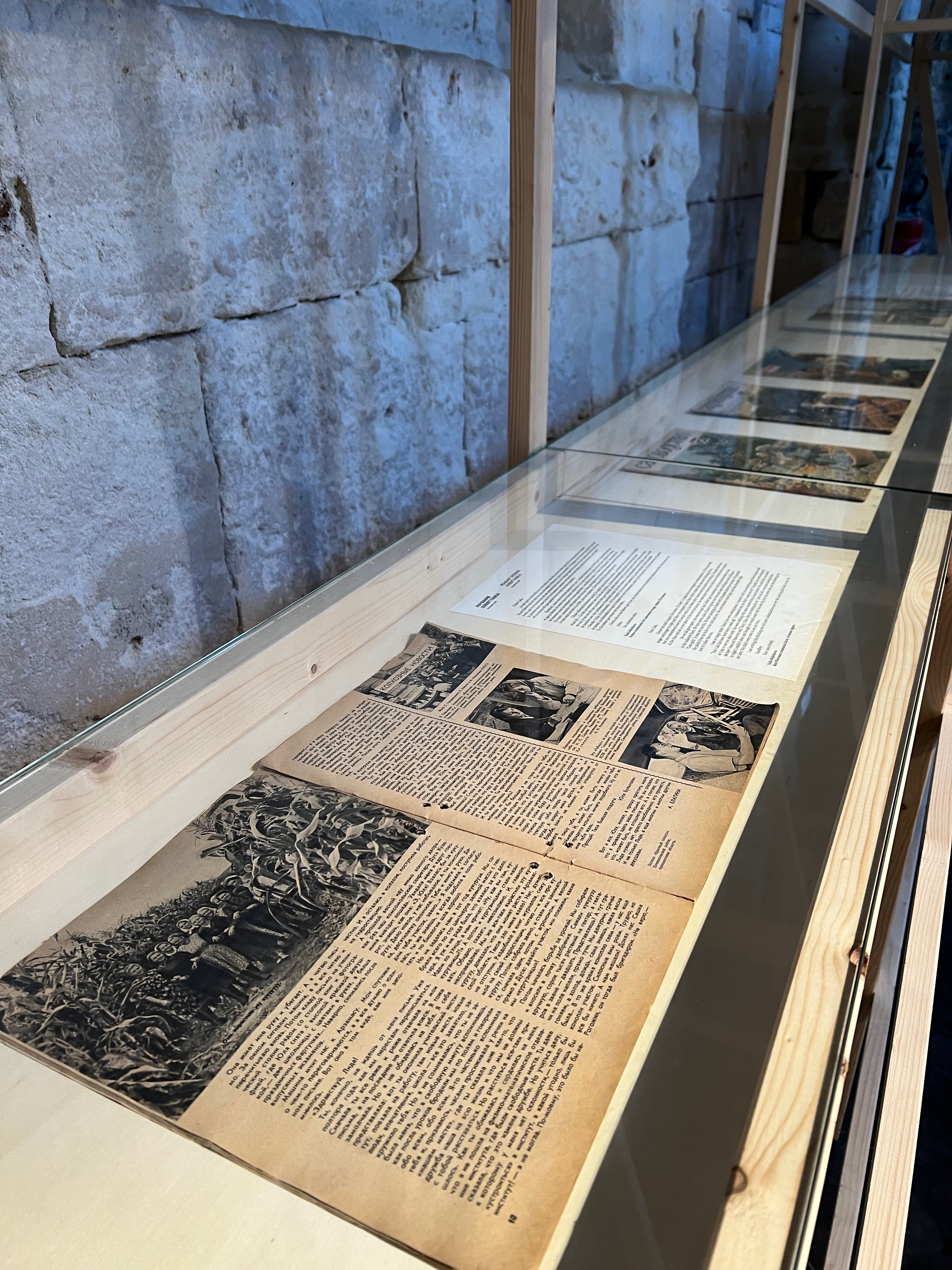

‘For the exhibition Our Grandmothers' Gardens, Olga Grotova tells the story of her ancestors and country using three media: a film, historical magazines, and two works on paper. The film recounts the artist’s return to the Ural Mountains with her mother. They go out to find a parcel of land that belonged to her great-grandmother in the Soviet era, then to her grandmother, ending up in collective ownership. The artist’s viewpoint on this space of true self-determination is a tribute to the agency of these women. In the archive, we see Soviet propaganda campaigns boasting of women farmers. Finally, completing the set, are two works on paper made by superimposing images and materials, notably that of earth taken from the gardens themselves.’

Taous Dahmani, Curator

Debris on a Luminous Plain

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art and MUAR, Moscow, 2021

Centrala, Birmingham, 2019

In present-day Russia there is an untold history of the hundreds of thousands of women who were executed or forcedly resettled to the Gulag, the system of forced labour camps across the Soviet Union. Many of them were wives and mothers of men pronounced the ‘Enemies of the People’ (Vragi Naroda): ethnic minorities, affluent peasants, academics, Germans, Jews and Poles that were thought a threat to the Soviet regime. The women were arrested at night, sentenced without trial and hauled to the country’s remotest regions. One of the biggest all-female penal facility was the camp for ‘Wives of the Traitors of the Motherland’ also known as ‘Algiers’ (А.Л.Ж.И.Р) where tens of thousands were detained, amongst them thousands of mothers with their small children.

Debris on a Luminous Plain is based on my grandmother’s memories of ‘Algiers’ and the Kazakh steppe where the camp was located. She arrived there in 1938 as a one-year old baby with her mother, my great grandmother, and they returned back to Russia twenty years later. The knowledge that rests in between those temporal indents is fractured and disjointed, akin to the slippages of the tongue that would incessantly fail to form a narrative.

In the recent decades the Russian state has done everything to obliterate the history of ‘Algiers’ and other forced-labour camps: they are not featured in history books and are not subjects of state-commissioned monuments and remembrance ceremonies. The female prisoners’ stories have been twisted and re-written to justify the ordeal, but mostly they have been silenced; instead they exist like worm tunnels that weave through the monolith of Russia’s history, filling it with voids and fractures.

Olga Grotova

Debris on a Luminous Plain (SOLO), Centrala, 2019

Olga Grotova

Fifth Wave, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Moscow Museum of Architecture, 2021

Olga Grotova

Debris on a Luminous Plain (Solo), Centrala, 2019

Olga Grotova

Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments on styrofoam, ceramics, Centrala, 2019

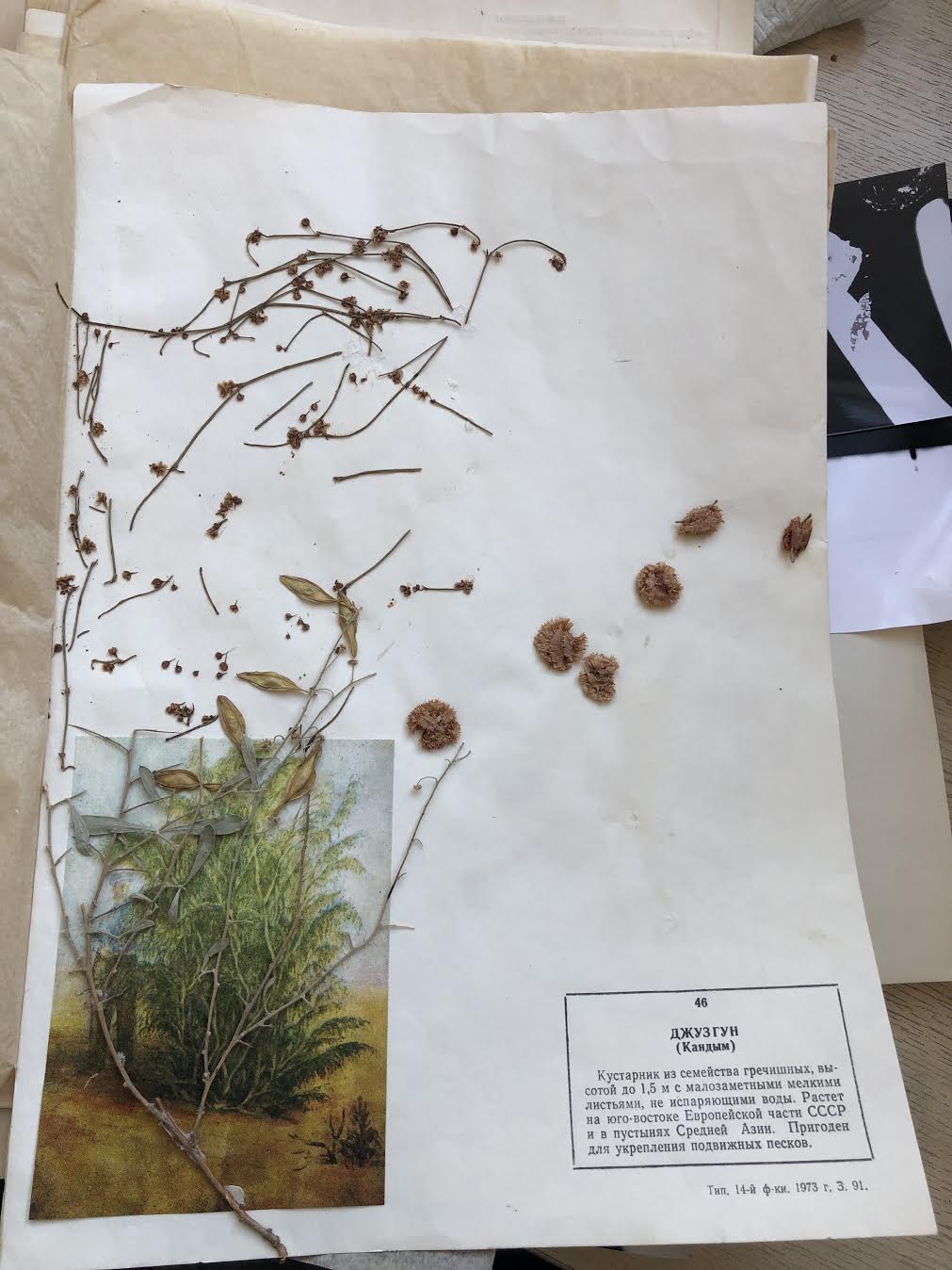

A few years ago I came across a 1970s herbarium on a Russian online noticeboard. Driven by an unclear instinct I asked my mother to buy it. Afterwards she reported that the seller was a middle-aged man who came in a car covered in patriotic stickers: ‘To Berlin!’ and ‘We’ll bend you over’. His wife was a schoolteacher, he said, she found the herbariums discarded in the school storage.It was an easy way to make a buck; his car was an old Zhigul.

I picked up the artefact next time I came to Russia: two massive boxes with hundreds of sheets of dried plants. The herbarium was a study material distributed widely in Soviet schools to educate the children about USSR’s vast territories: from the newly adjoined Asian republics to Siberia and Caucasus. Each plant had a name a naïve illustration next to it showing the scene from the place where it had been collected: a woman harvesting grapes in Crimea, a man walking the donkey in one of the East Asian countries.

One of the herbarium’s chapters was about the Kazakh steppe. It had some weeds whose names I heard from my grandmother: sagebrush, feather brush. The illustration showed a smiling man in a wide-brimmed straw hat with the yolk-yellow deserted landscape in the background.

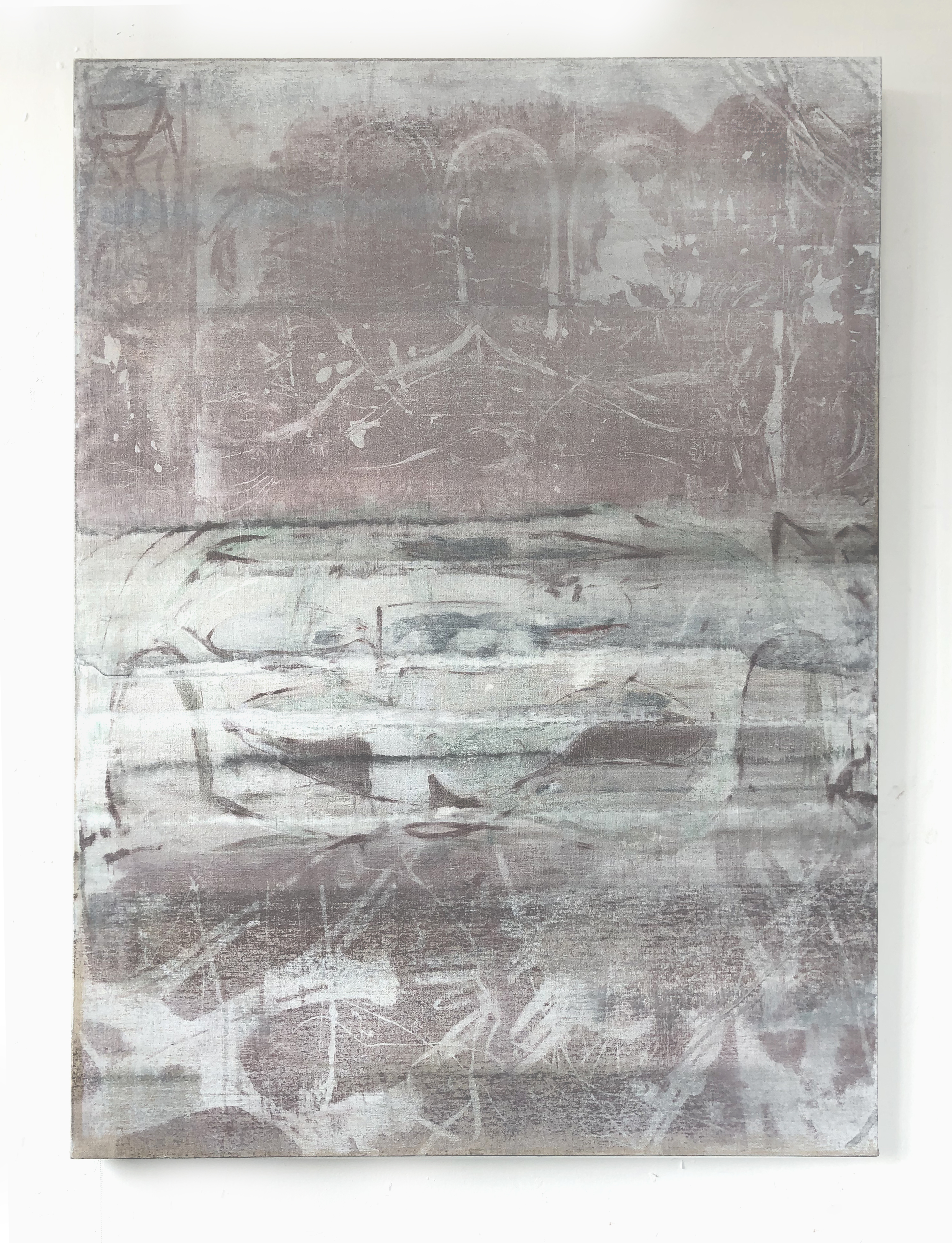

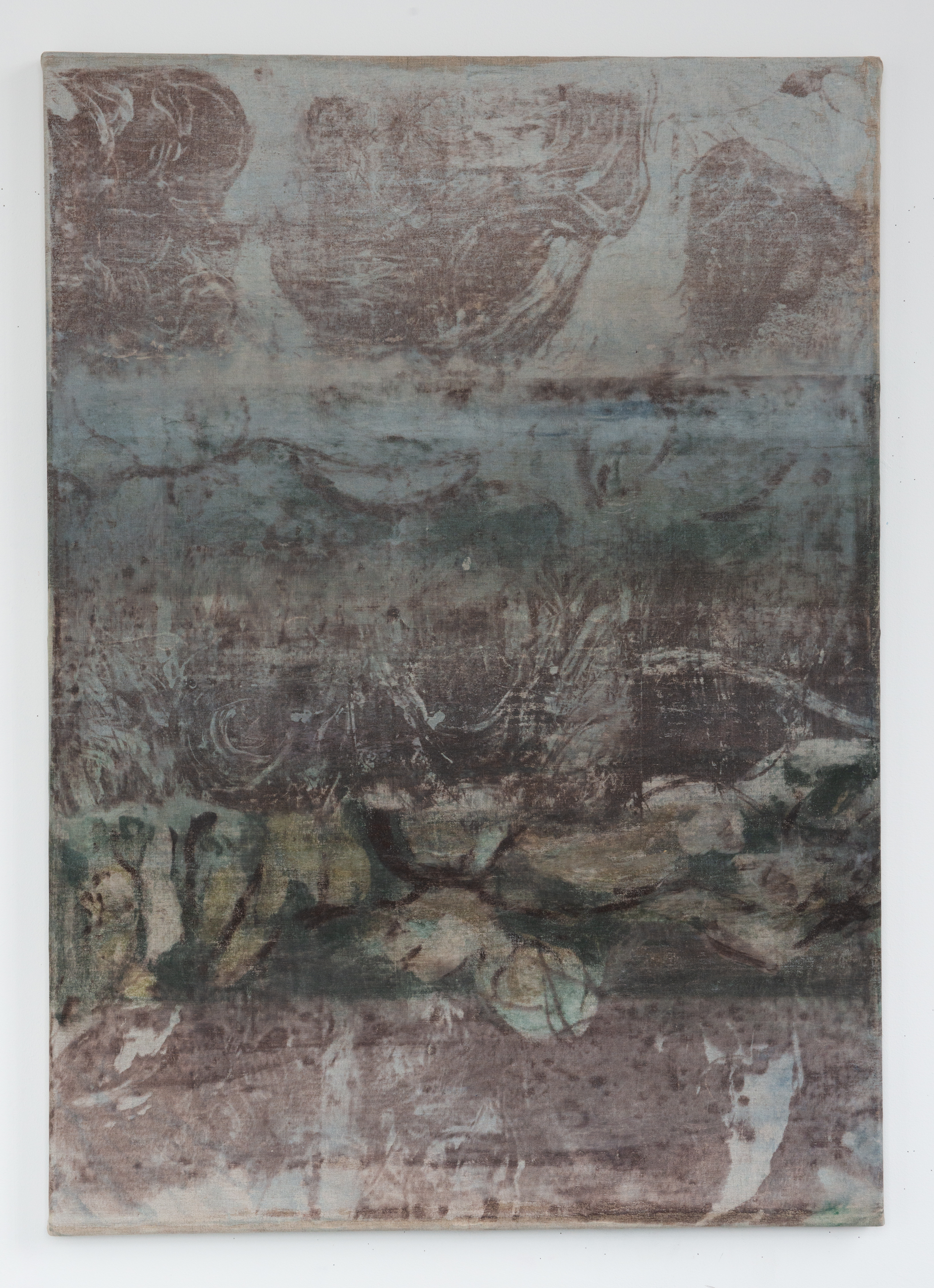

The Debris paintings are made with the traces of the Kazakh steppe plants: a laborious mark-making process that I developed to replace my agency with that of the non-human witnesses. Each painting is an exercise in accumulating absences, layering them one after another to contain a narrative within silences.

Olga Grotova

Fifth Wave, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Moscow Museum of Architecture, 2021

Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments and imprints of steppe weeds, on linen

Olga Grotova

Fifth Wave, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

Moscow Museum of Architecture, 2021

Olga Grotova

Debris on a Luminous Plain, performance, Centrala, 2019

Olga Grotova, Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments and imprints of steppe weeds, on linen, 170 x 120 cm, 2019

Olga Grotova, Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments and imprints of steppe weeds, on linen, 170 x 120 cm, 2019

Olga Grotova, Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments and imprints of steppe weeds, on linen, 170 x 120 cm, 2019

Olga Grotova, Debris on a Luminous Plain, pigments and imprints of steppe weeds, on linen, 170 x 120 cm, 2019

Arches and Vessels, 2021

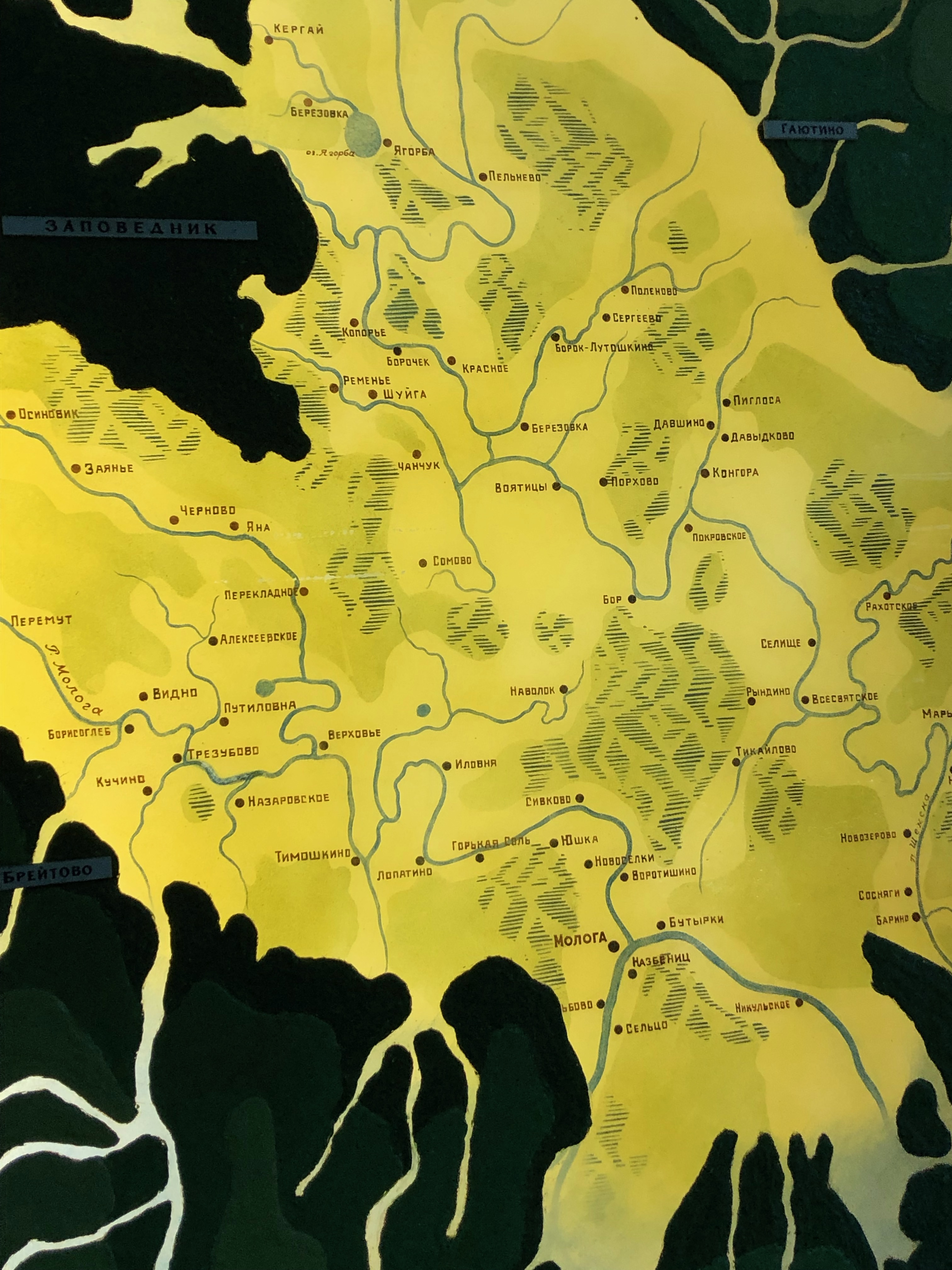

‘Arches and Vessels’ is a series of works informed by the journey to my great grandmother’s birthplace ‘Fishtown’ on the Volga River.

The valley surrounding the town was submerged during the construction of the hydroelectric station in the 1930s and became the world’s largest artificial sea; tens of thousands were displaced and the ecology of the region and the harvests have been permanently altered by the cool climate brought on by the large body of water.

One of the sites destroyed during the station’s construction was a Leushin female monastery visited and documented by Prokudin-Gorsky, a historic church complex whose frescoes have been submerged under the reservoir’s waters.

Olga Grotova

Photograph of the ‘Fishtown’ sea, 2019

The map of the drowned valley, 2019

Olga Grotova

The Path of Volga, pigments on paper, 2020

Olga Grotova

The Path of the Volga (three cups), pigments on linen, 150 x 110 cm, 2021

The Path of the Volga (three cups), pigments on linen, 150 x 110 cm, 2021

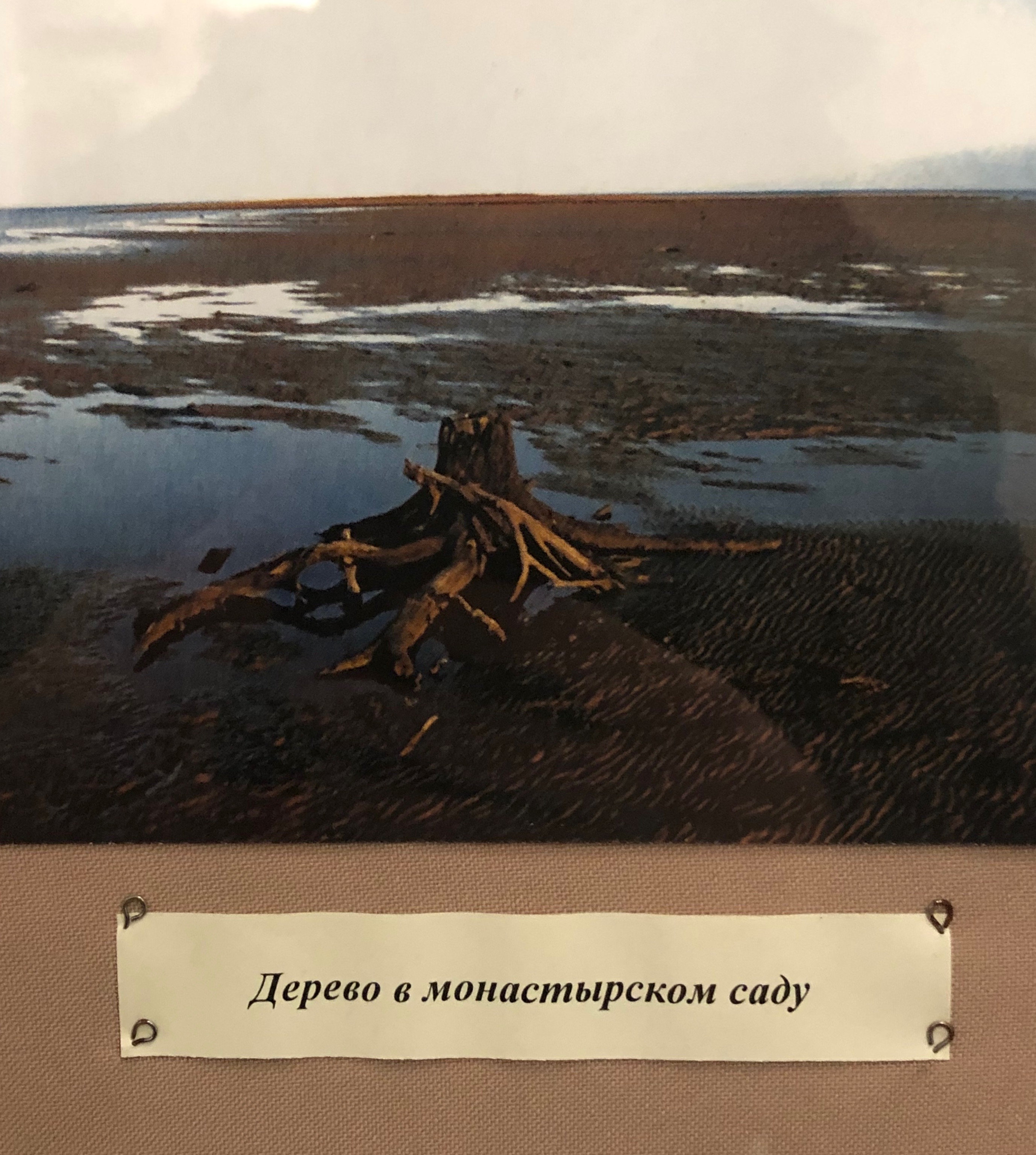

The tree in the monastery garden

Olga Grotova

The Path of Volga, pigments on paper, 2020

Olga Grotova

Path of Volga (caves), pigments on linen, 150 x 110 cm, 2021

Path of Volga (caves), pigments on linen, 150 x 110 cm, 2021

Olga Grotova

The Path of Volga (Shells), pigments on linen, 110 x 90 cm, 2021

The Path of Volga (Shells), pigments on linen, 110 x 90 cm, 2021

The Waters of the Volga

Oslo Kunstforening, 2019

Curated by Praksis

The project is based on my poem about a trip to the Volga River, my great grandmother’s birthplace. Performed in collaboration with Syowia Kyambi at the Oslo Kunstforening.

The series of drawings is made with river waters, debris and graphite.

Olga Grotova and Syowia Kyambi

The Waters of the Volga

Performance, Oslo Kunstforening, 2019

Olga Grotova

‘The Waters of the Volga’

Pigments and river waters on paper

Oslo Kunstforening, 2019

Olga Grotova

‘The Waters of the Volga’

Installation view

Oslo Kunstforening, 2019

XVII. The Age of Nymphs

Mimosa House, London, 2018

Curated by Daria Khan

XVII. The Age of Nymphs explores human and insect affects and the archaeology of trauma. The exhibition looks to cycles of history and the possibility of reanimating time through repetition and doubling. Confronting the stagnation of the current times, the artists test posthuman gestures and insect behaviours as a challenge to human politics.

Olga Grotova

XVII. The Age of Nymphs

Installation view

Mimosa House, 2017

Olga Grotova

The Ice Rink, 2017

Video, sound

9’ 30’’

DARIA KHAN to OLGA: The two protagonists of ‘The Ice Rink’ remind me both of Chekhov’s ‘Three sisters’ and Bergman’s ‘Persona’. Isolated, stuck and lost thus living in a blissful oblivion, they reflect one another in what they say and do. Their closeness suggests sexual tension (reinforced by phallic figures of the big chocolate key and the potentially injuring icicle).

I am interested in the physical and the transcendental elements of the work. The ritual involving the chocolate key and the protagonists’s attire of catholic nuns references a history of the bodily vs. the spiritual. What does this mean for you in the context of this exhibition?

OLGA: The characters in The Ice Rink are positioned inside the space of the digital video: a disembodied, timeless and transcendent form of representation. Their unnatural and overtly feminine screen makeup echoes old cinematic conventions, an era when film possessed materiality. To make cuts in the celluloid is a different montage process compared to the contemporary video editing, which allows constant rearranging and duplication. In the film one of the characters mentions the surface carved by the blades echoing both the surface of ice and the physical film, which is missing.

The conflict between the physical and the transcendent has long occupied the Christian tradition and has been dealt with through rituals, which use language as means to escape corporal reality. Fasting and celibacy are the means for the expelling of the bodily excess. The body however returns as the body of Christ in the Eucharist. In the film it is acted out with a chocolate key. As Kristeva puts it: “By the very gesture...that corporealizes or incarnates speech, all corporeality is elevated, spiritualized, and sublimated.”

The First Reading

Performance in collaboration with Luli Perez

Mimosa House, 2018

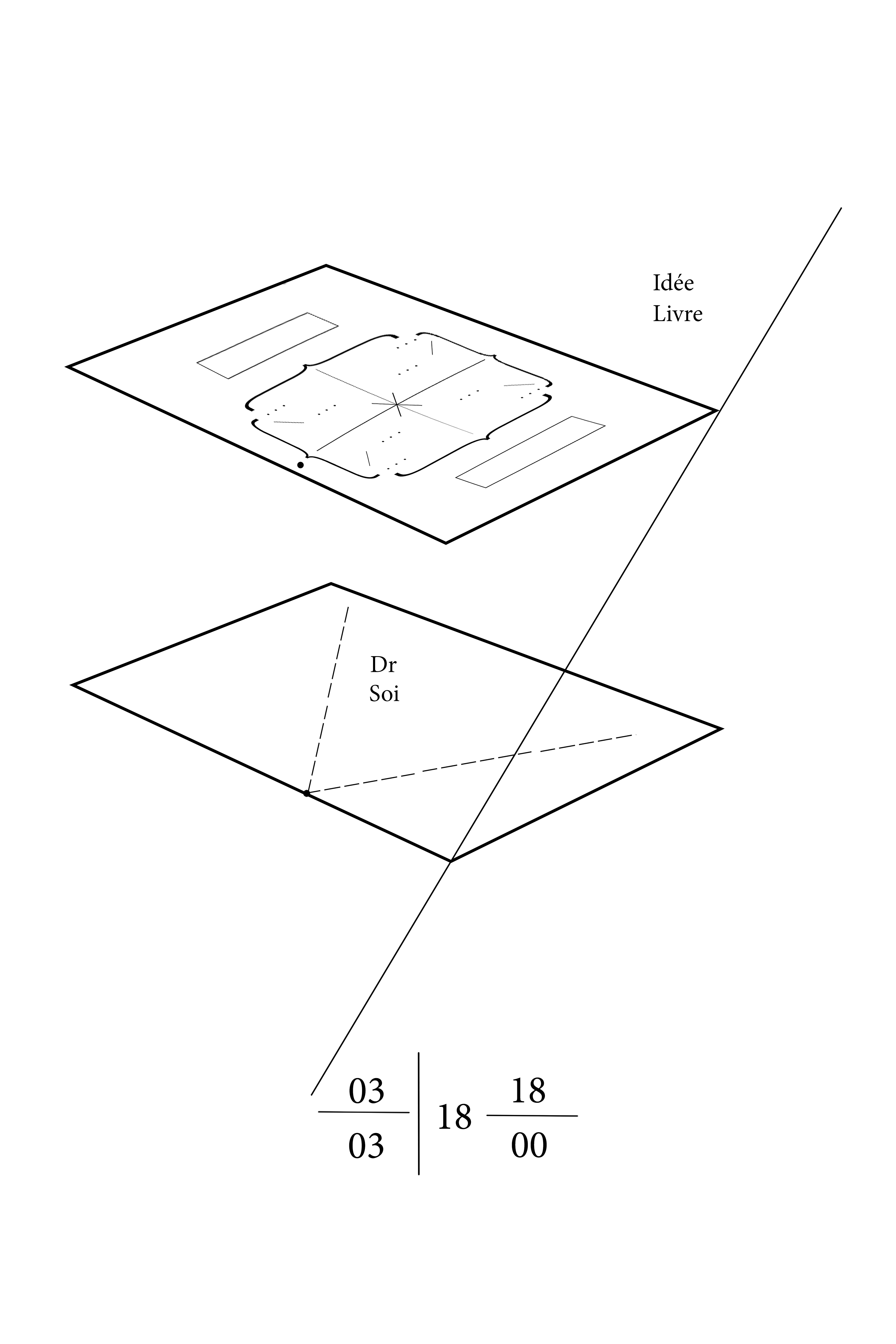

Performance, discussion and video in which 4 performers or readers enact Le Livre, Stéphane Mallarmé’s unpublished magnum opus over three operations.

The event is split between the two rooms, which are located one on top of the other. The board game takes place in the room upstairs where the viewers are invited to record the players with a camera that produces a live feed on the screen in the room below. The audience can thus observe the Reading either on the screen or in person, but can never access both at the same time.

Blue. Seventeen

Osnova Gallery, Moscow, 2017

Curated by Sasha Burkhanova-Khabadze

Soon there will be doubles of all the decades. In forty-five years, as the human lifespan keeps increasing, one will think of the 60s as of the 2060’s and the 1960s. Thus occurs a doubling of history, déjà vu and ultimately a return to a non-existent point in the past. In 1917 there was a Russian revolution. Thus Russians still refer to it as ‘The revolution of the year seventeen’, but as of next year it will mean both 1917 and 2017. The suspended, circular, state of contemporary gives rise to political myths and an idea of reanimation of time. My work tends to merge political facts and personal experiences, reality and fiction, rehearsal and performance. The viewer is often disoriented when trying to determine fiction ends and reality starts.

Olga Grotova (with Nika Neelova and Yelena Popova)

Blue. Seventeen

Installation view

Osnova, 2017

Olga Grotova

Seventeen

Acrylic on canvas, 150 x 110

2017

Olga Grotova

Blue. Seventeen

Installation view

Osnova, 2017