Debris on a Luminous Plain

Centrala, Birmingham (Solo exhibition)

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

2019- 2021

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art

2019- 2021

In present-day Russia there is an untold history of the

hundreds of thousands of women who were executed or forcedly resettled to the

Gulag, the system of forced labour camps across the Soviet Union. Many of them

were wives and mothers of men pronounced the ‘Enemies of the People’ (Vragi

Naroda): ethnic minorities, affluent peasants, academics, Germans, Jews and

Poles that were thought a threat to the Soviet regime. The women were arrested

at night, sentenced without trial and hauled to the country’s remotest regions.

One of the biggest all-female penal facility was the camp for ‘Wives of the Traitors

of the Motherland’ also known as ‘Algiers’ (А.Л.Ж.И.Р) where tens of thousands were detained, amongst them

thousands of mothers with their small children.

In the recent decades the Russian state has done everything to obliterate the history of ‘Algiers’ and other forced-labour camps: they are not featured in history books and are not subjects of state-commissioned monuments and remembrance ceremonies. The female prisoners’ stories have been twisted and re-written to justify the ordeal, but mostly they have been silenced; instead they exist like worm tunnels that weave through the monolith of Russia’s history, filling it with voids and fractures.

Debris on a Luminous Plain is based on my grandmother’s memories of ‘Algiers’ and the Kazakh steppe where the camp was located. She arrived there in 1938 as a one-year old baby with her mother, my great grandmother, and they returned back to Russia twenty years later. The knowledge that rests in between those temporal indents is fractured and disjointed, akin to the slippages of the tongue that would incessantly fail to form a narrative.

In the recent decades the Russian state has done everything to obliterate the history of ‘Algiers’ and other forced-labour camps: they are not featured in history books and are not subjects of state-commissioned monuments and remembrance ceremonies. The female prisoners’ stories have been twisted and re-written to justify the ordeal, but mostly they have been silenced; instead they exist like worm tunnels that weave through the monolith of Russia’s history, filling it with voids and fractures.

Debris on a Luminous Plain is based on my grandmother’s memories of ‘Algiers’ and the Kazakh steppe where the camp was located. She arrived there in 1938 as a one-year old baby with her mother, my great grandmother, and they returned back to Russia twenty years later. The knowledge that rests in between those temporal indents is fractured and disjointed, akin to the slippages of the tongue that would incessantly fail to form a narrative.

Debris on A Luminous Plain

Centrala, 2019

Debris on A Luminous Plain, performance

Centrala, 2019

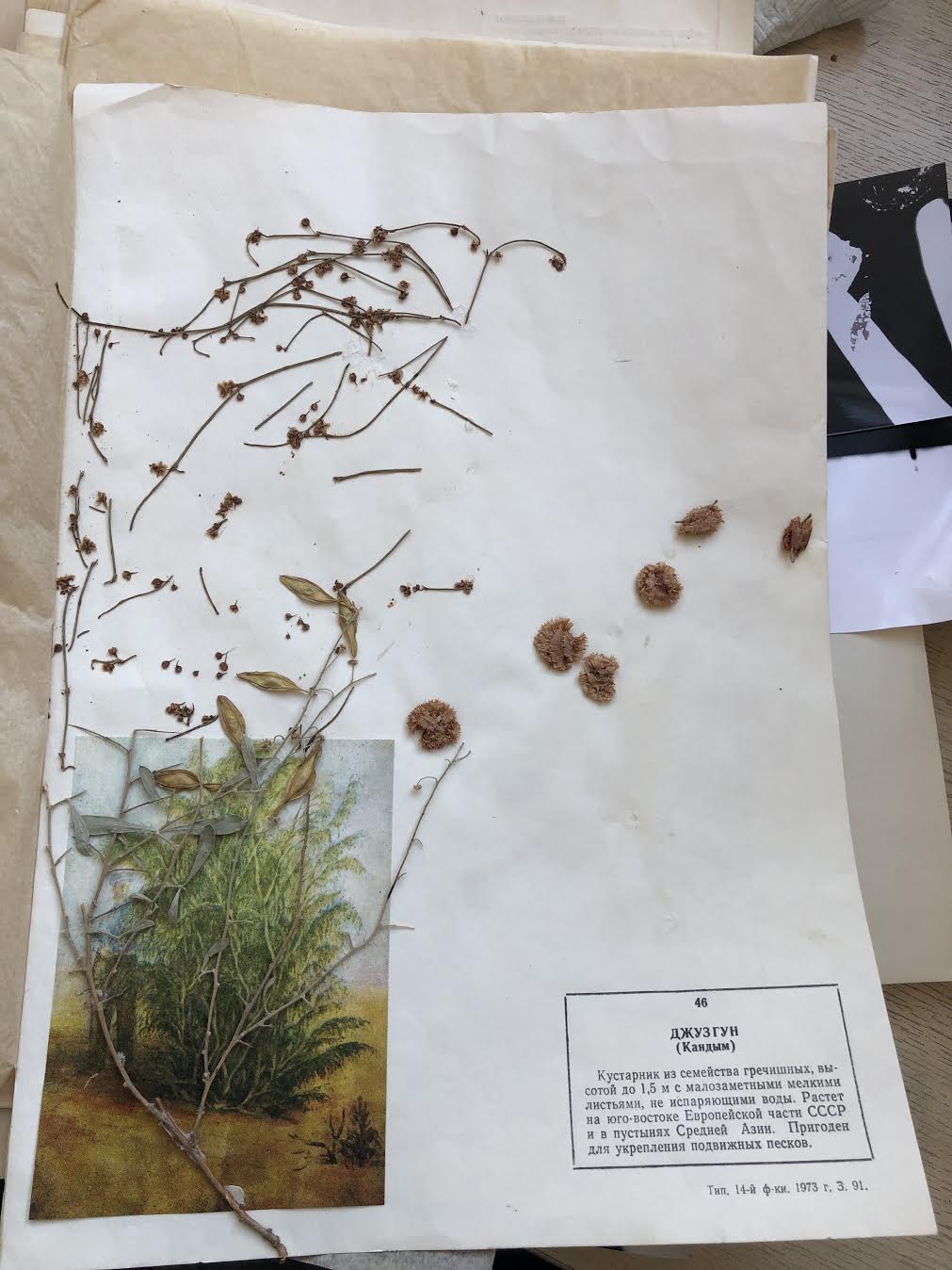

A few years ago I came across a 1970s herbarium on a Russian online noticeboard. Driven by an unclear instinct I asked my mother to buy it. Afterwards she reported that the seller was a middle-aged man who came in a car covered in patriotic stickers: ‘To Berlin!’ and ‘We’ll bend you over’. His wife was a schoolteacher, he said, she found the herbariums discarded in the school storage.It was an easy way to make a buck; his car was an old Zhigul.

I picked up the artefact next time I came to Russia: two massive boxes with hundreds of sheets of dried plants. The herbarium was a study material distributed widely in Soviet schools to educate the children about USSR’s vast territories: from the newly adjoined Asian republics to Siberia and Caucasus. Each plant had a name a naïve illustration next to it showing the scene from the place where it had been collected: a woman harvesting grapes in Crimea, a man walking the donkey in one of the East Asian countries.

One of the herbarium’s chapters was about the Kazakh steppe. It had some weeds whose names I heard from my grandmother: sagebrush, feather brush. The illustration showed a smiling man in a wide-brimmed straw hat with the yolk-yellow deserted landscape in the background.

The Debris paintings are made with the traces of the Kazakh steppe plants: a laborious mark-making process that I developed to replace my agency with that of the non-human witnesses. Each painting is an exercise in accumulating absences, layering them one after another to contain a narrative within silences.